Science Of Hallucinations

What is a hallucination?

Hallucinations are sensory experiences of perceiving something that is not there. Hallucinations can involve any of the senses, such as hearing, seeing, touching, smelling, tasting, or sensing the presence of people or things that other people do not.

Hallucinations may share similarities to related concepts, like “illusions”, “misperceptions”, “dreams”, or “imagination”, but hallucinations are a distinct category of mental life. In general, hallucinations feel real, are experienced without voluntary control, and occur in the waking state – though specific types of hallucinations occur when falling asleep (“hypnagogic hallucinations”) or waking up (“hypnopompic hallucinations”).

Hallucinations are sometimes described as part of “psychosis”, a broader term that refers to hallucinations and delusions (holding strong beliefs that others don’t share).

Some people might find other terms more helpful in describing this experience, such as “hearing voices”, “voice-hearing” or “seeing visions”. This website uses the term “hallucination” to acknowledge the plurality and breadth in their content and meaning.How common are hallucinations?

What is it like to experience hallucinations?

There is considerable variation in what it is like to experience hallucinations, in terms of the content of the hallucination, the sense(s) involved (ie., hearing or seeing), the emotions or feelings experienced, the frequency of hallucinations, and the circumstances in which hallucinations arise.

One way in which researchers study the subjective experience (or “phenomenology”) of hallucinations is through interview, asking people open-ended or structured questions about their hallucinations. These studies show that people with schizophrenia often report hearing voices or sounds, which may be commanding or abusive, but may also be commenting in a neutral way, or sometimes positive, and some hallucinations may be experienced more as intrusive thoughts than audible voices. On the other hand, people with Parkinson’s disease who experience hallucinations often report seeing groups of people, children, animals, or shadowy shapes or figures. An online survey about voice-hearing experiences completed by people with and without a diagnosis showed that there is high diversity in hallucinatory experiences. For instance, 66% of voice hearers reported an accompanied bodily sensation, such as feeling heat, or tingling, and 69% reported voices with personalities.

Hallucinations can occur in more than one sense at the same time – called “multisensory hallucinations” – which may be twice as common as hallucinations in one sense alone for people with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder. The primary sense involved also varies by clinical diagnosis. For example, one study of 100 people with schizophrenia and 100 with Parkinson’s disease, each experiencing hallucinations, showed that 83% of people with schizophrenia had auditory hallucinations and 55% had visual hallucinations, whereas 45% of people with Parkinson’s had auditory hallucinations and 88% had visual hallucinations. Hallucinations are often accompanied by feelings, such as confusion, fear, frustration, anxiety, distress, loneliness, or positive feelings, mild amusement or a spiritual experience. In any case, hallucinations can feel very real.

A challenge felt by many people in sharing their experiences is the stigma and public misunderstanding surrounding hallucinations. Many people worry that if they share their hallucinations with family, friends, doctors, or nurses, they might be labelled as mentally ill, unstable, or violent. This stigma may prevent people from disclosing their experiences and seeking help if they find their hallucinations distressing.

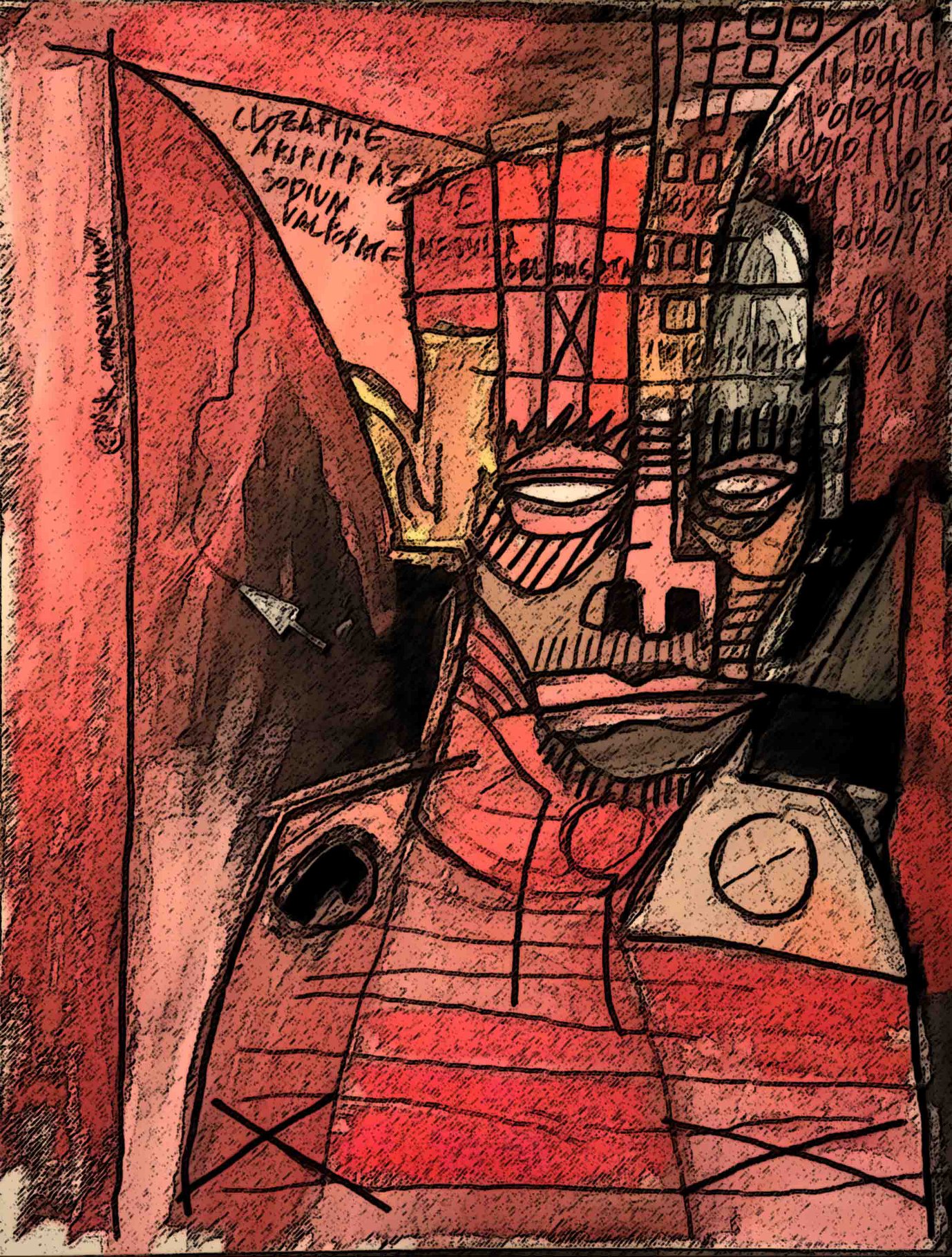

Why do people experience hallucinations?

There is no single reason why people experience hallucinations. Risk factors for hallucinations can be social, environmental, neurobiological, genetic, or an interaction between one of more of these factors, and risks vary depending on whether a person has a clinical history.

Risk factors for hallucinations in Parkinson’s include: certain types of medication, sleep disturbances, impaired vision, stage of illness, depression, and memory difficulties.

Risk factors for hallucinations or psychosis in schizophrenia include: negative life experiences, such as trauma, ethnic minority status, growing up in an urban compared to rural environment, and poverty or social adversity.

Biological factors can also play a role in hallucinations, including neurochemical factors like dopamine, and the organization of structural and functional connections in the brain.

Human brains assess and process information from both the sensory world and past experiences together to make sense of what people perceive. Current psychological and neuroscientific theories suggest that errors in how the brain processes information may cause hallucinations. For example, one theory suggests that people may have auditory hallucinations or hear voices when the brain doesn’t recognize their inner dialogue (or “inner speech”) as their own.

How common are hallucinations?

Hallucinations occur in a wide range of psychiatric, neurological, and medical conditions, but many healthy people may also experience hallucinations at some point in their lives.

For people with a psychiatric diagnosis, hallucinations are reported by 60 to 80% of people with schizophrenia, 43% of people with a personality disorder, and 34% of people with bipolar disorder.

For people with a neurodegenerative condition, hallucinations are reported by 28% to 75% of people with Parkinson’s disease, depending on the stage of illness, 62% of people with Lewy Body dementia, and 23% of people with Alzheimer’s disease.

For people without a clinical diagnosis, research studies show that roughly 5% of the general population have experienced a hallucination during their lifetime. This estimate ranges from 3–13%, depending on the age group studied.

Hallucinations can also be brought about by stress, bereavement, drug use, sleep loss, traumatic events, or sensory deprivation.

A hallucination is not in itself a sign of a mental health or medical problem. For some people, hallucinations can be very distressful; for others, they may be positive or contribute to meaningful experiences; and yet for others, they may be benign or neutral.

What is the brain basis of hallucinations?

Hallucinations have long fascinated neuroscientists and psychologists since they offer a window to understanding the nature of perception. Advances in brain imaging methods in the last two decades or so (magnetic resonance imaging, MRI, and functional MRI, fMRI) have allowed scientists to map the brain regions associated with hallucinations in different medical conditions.

There are two ways to study the brain basis of hallucinations: the first is “state studies”, which investigate what is happening in the brain while a person is hallucinating, and the second is “trait studies”, which investigate the activity or structure of the brain in people who tend to hallucinate, compared to people who do not hallucinate.

A systematic and quantitative review of trait studies in the scientific literature by our study team demonstrated that brain anatomy associated with hallucinations in psychiatric disorders, like schizophrenia, is entirely distinct from that associated with neurodegenerative disorders, like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease. For example, hallucinations experienced by people with a psychiatric diagnosis were associated with grey matter changes in speech and language regions (known as the superior and middle temporal gyri, inferior frontal gyrus), the medial anterior cingulate cortex and insula, while hallucinations in Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease were associated with grey matter changes in the visual cortex and thalamus.

This research suggests that there is more than one way in which the brain produces hallucinations, and these different brain mechanisms might be linked to why people have different experiences of hallucinations.